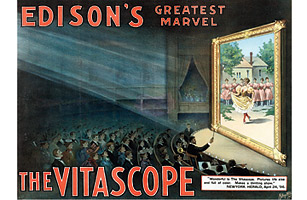

Though Edison didn't invent the Vitascope, his company manufactured and marketed it

Toward the end of MGM's 1940 biopic Edison, the Man, starring Spencer Tracy, an honor roll of Thomas Edison's achievements marches onto the screen: Fluoroscope! Mimeograph! Storage battery! And then to the heart of the matter for the film industry: Motion pictures! Projection machine! Talking pictures! In its golden age, Hollywood was paying tribute to the man who, nearly a half-century earlier, possessed the genius and foresight to invent the movies.

It wasn't that simple a story. The movies love a lone hero, and Edison was a natural for Hollywood hagiography. One of his most enduring inventions was the very notion of the inventor as American superman, with himself in the lead role. But the birth of movies had many obstetricians. Etienne-Jules Marey and the Lumière brothers in France, William Friese-Greene in Britain, Eadweard Muybridge in the U.S. — these and others contributed to the "invention" of movies. So did some of Edison's employees, who were obscured by their boss's starlight.

The Wizard of Menlo Park talked a good line. In 1888 he announced that he was working on "an instrument which does for the eye what the phonograph does for the ear." Within a few years, he and his associates had developed a movie camera, known as the kinetograph, and a device for watching films, the kinetoscope. The use of 35-mm film and sprockets to secure it in the camera was also an innovation of his company. Edison's movies include some of the best-known titles in early cinema, among them The Kiss, Fatima's Dance and The Great Train Robbery. Experimenting with sound, color and special effects in a variety of genres, they are the clear ancestors of the next century of films.

Historians still debate the extent of the founder's participation in the process. What's unquestioned is Edison's erroneous belief that the future of movies lay in his peep-show kinetoscope, which allowed only one viewer at a time, rather than in images projected on a screen before a large audience. Edison's 19th century toy, showing short films of watermelon-eating contests and cats with boxing gloves, was really the harbinger of a 21st century novelty: YouTube.

For Edison, the invention of movies was a diversion from his main interest at the time: extracting iron ore from depleted mines, an obsession that would cost him much of his fortune. If that scheme had not so occupied him, he might not have left the bulk of the film-experiment work to his chief assistant, William Kennedy Laurie Dickson.

That proved to be the cinema's good fortune, for Dickson was a scientist with a gift for the theatrical. (The invaluable Kino DVD Edison: The Invention of Movies includes dozens of Dickson's early films.) It was probably he who designed Edison's film studio in West Orange, N.J., the Black Maria, a shack that revolved to catch the sun through a skylight. The world's first film director, Dickson also invested his experiments with odd touches that, seen today, look like infant epiphanies.

In Blacksmith Scene, which on May 9, 1893, became the first kinetoscope production to be shown publicly, Dickson presents three men wrapped in smithy aprons, their sleeves rolled up, rhythmically pounding an anvil with hammers. These first film actors (they were Edison Co. employees) pause to take swigs from a beer bottle, then return to work. Initially, the man on the left is partly obscured by a figure facing the action; he realizes he's in the way and ducks out of frame eight seconds into the 26-second film. So the first movie also had the first blooper.